What is the best method for learning a language? What if I tell you there is one that makes you fluent with 100% success rate? It is the method employed by everyone who was ever born into this world: virtually every child learns at least one language. You did too.

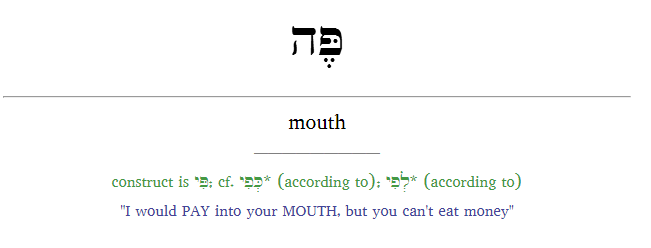

The brain has an innate ability to find patterns. A child learns fairly quickly how to ask for food and how to summon the mother or father, without thinking about imperatives, jussives or cohortatives.

You learn the grammar of your native language long after you are already fluent.

Surprisingly, language courses commonly begin with many grammar phenomenons. I can hardly think about a more discouraging way to teach than to dump complex conjugation tables on the student’s head. I actually experienced a Latin course for beginners where you were given three verb conjugations in three tenses to memorize – in the very first lesson! I could see the despair in my classmates. Is this some kind of sadistic torture?

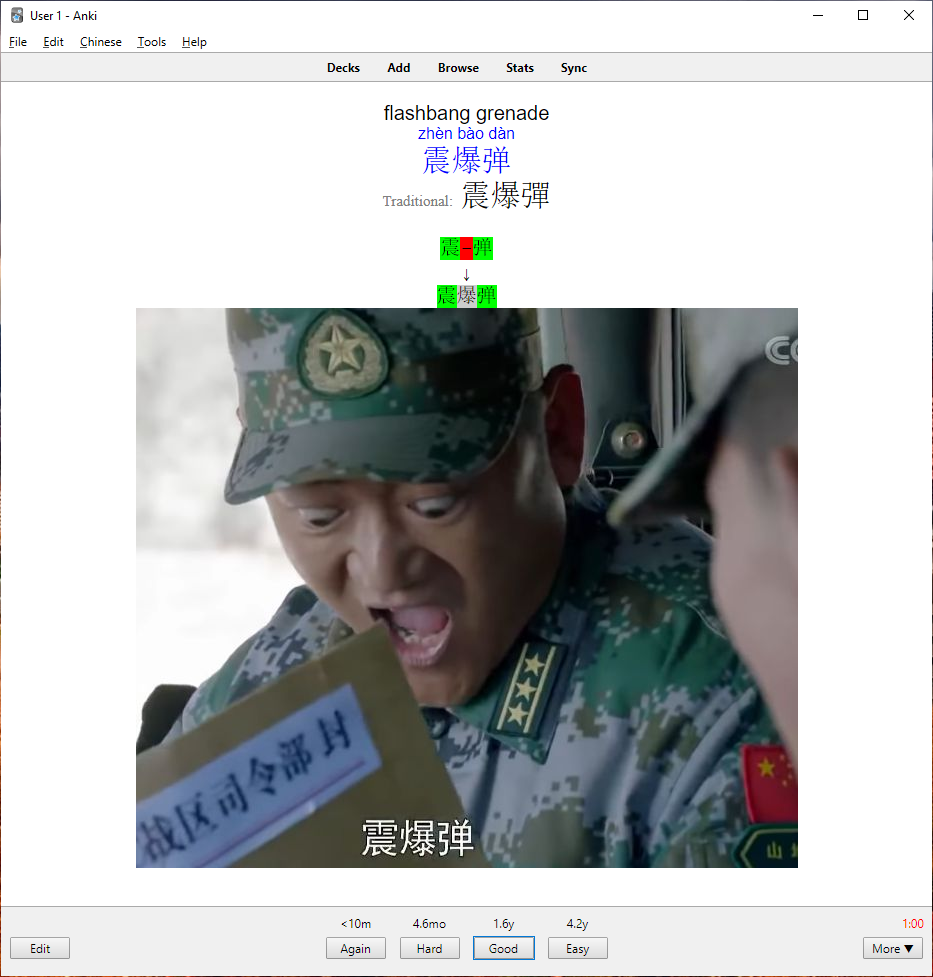

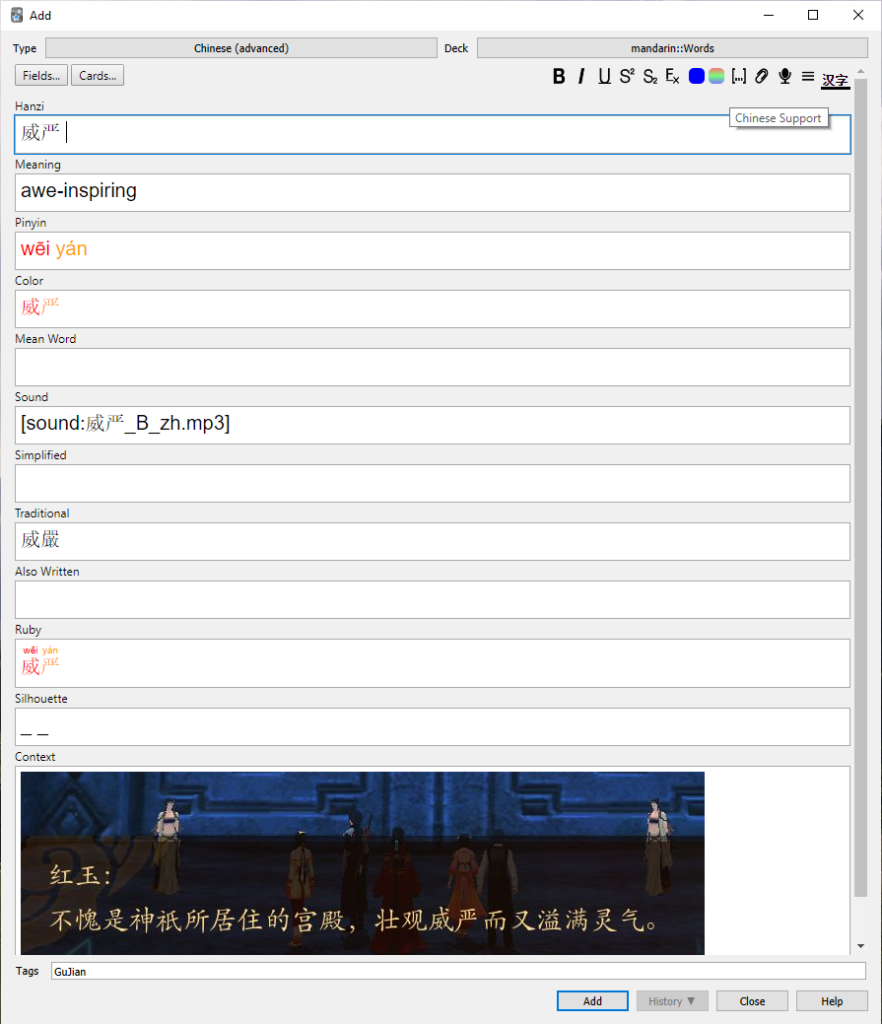

Don’t take me wrong, it is great to have grammar references. I am just arguing to reverse the order. Just do what you did with your very first language – expose yourself to a lot of real world input. And learn grammar only when you already start seeing the pattern in the real world (e.g., what’s the “te” suffix I see in every second German sentence?). You will discover the patterns that will actually make you curious to check the grammar. It will be very enjoyable: you will experience eureka effect a lot when you simply corroborate what you (almost) figured out already. It will be much easier to memorize a rule when you’ve seen a hundred times before.

How ridiculous is it to have a solution that works (the way you learned your native language) and then do something else that doesn’t work instead? Why would you choose pain instead of having fun, when having fun is actually better for reaching your goal? They key is to expose yourself to as much of your new language as possible, without getting overwhelmed and still having fun.

Books (text with audio) are in my experience the most effective (at least for the passive skill) but also quite draining – I find it too hard to read books in a language I am learning for more than a couple hours in day. That’s where movies (and videogames) with subtitles come in. They less effective (in the terms of language improvement relative to time spent), but when you’re too tired to open a book, it might be the way to go.

This rant is in no way new. Aurelius Augustine (who lived in the fourth century) also noticed this difference between from “grammarians” (basically Greek slaves who would beat you until you got it right) and from nurses (“between blandishments and kisses” – BTW. that makes me think of a very powerful way to get motivated in learning a language – but let’s leave that for another post 🙂 ).

But what were the causes for my strong dislike of Greek literature, which

Augustine, Confessions, Liber I

I studied from my boyhood? Even to this day I have not fully understood them. For Latin I loved exceedingly–not just the rudiments, but what the grammarians teach.

But why, then, did I dislike Greek learning, which was full of such tales?

For Homer was skillful in inventing such poetic fictions and is most sweetly wanton; yet when I was a boy, he was most disagreeable to me. I believe that Virgil would have the same effect on Greek boys as Homer did on me if they were forced to learn him. For the tedium of learning a foreign language mingled gall into the sweetness of those Grecian myths. For I did not understand a word of the language, and yet I was driven with threats and cruel punishments to learn it. There was also a time when, as an infant, I knew no Latin; but this I acquired without any fear or tormenting, but merely by being alert to the blandishments of my nurses, the jests of those who smiled on me, and the sportiveness of those who toyed with me. I learned all this, indeed, without being urged by any pressure of punishment, for my

own heart urged me to bring forth its own fashioning, which I could not do except by learning words: not from those who taught me but those who talked to me, into whose ears I could pour forth whatever I could fashion. From this it is sufficiently clear that a free curiosity is more effective in learning than a discipline based on fear.

So go to librivox or youtube – get the audiobook, google the text for it and a translation and get going!